CIRCUS

MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1973

Written

by Steve Gaines

- 'Foreigner’

- Cat

Puts An End To‘The Cat Stevens Sound’

"I

don’t want to go on playing predictable

me,’ Cat said impatiently in his white

London house. "I’ve got to introduce

an element of shock."

The

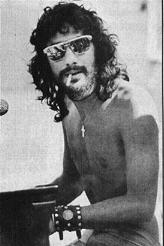

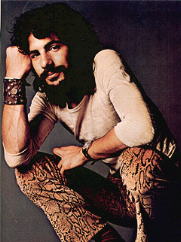

cat is not just back, the Cat us black. Mr.

Moonshadow Stevens was sitting at the end

of a long brown sofa in the London office

of Island Music lightly stroking the ends

of his shaggy beard as he spoke. Slim, intense,

and magnetically attractive, his conversation

had drifted to his last United States tour.

"The tour turned me around several times,"

Stevens said, his dark brown eyes staring

at an upright piano on the wall opposite him.

"After leaving the States I sat down

to ponder what I had been doing and I realized

I’d been gradually getting into a very

predictable state." The results? "I

said I’ve got to stop this and introduce

an element of shock."

Only

a man of Cat Stevens aspirations would feel

that his present position cried out for a

revitalizing jolt. With four gold albums tucked

under his arm, no one else imagined his career

as boring. Yet shortly after returning to

his London home last fall, Cat Stevens decided

to throw away the musical formula that had

made him into a superstar in three short years.

Along with his lavish orchestrations and violins,

Stevens dropped guitarist Alun Davies and

bassist Alan Jones to emerge with a fifth

album that is as radically different from

his previous LP’s as it is brilliant.

Bitter

brawn sugar: Aptly titled Foreigner (on

A&M Records) the album is a total departure

from the sweetly melodious past into driving

R&B music. Not only did the Cat record

Foreigner in

Kingston, Jamaica, but he employed an all

black group of session musicians and a trio

of wailin’ black girls who could give

a dozen Merry Claytons stiff competition.

But why did the Boy who Loves his Dog cross

the color line into R&B? The story has

its roots back in September of 1970. When

a naive and emerging pop star first arrived

among the concrete towers of Manhattan isle.

"I

had a romantic, delightful image of New York,

and suddenly I got there and couldn’t

believe the aggression that was going on."

From behind the tinted windows of a black

limousine, he watched the people wander through

the dirty streets of the city, unsmiling,

hostile, lost. Later that night he sat in

the whipped cream luxury of a suite at the

St. Regis Hotel and penned the lyrics for

a song that sowed the seeds of Foreigner.

- How

many times must I get up

- Look

out and see the same old view

- How

many times must I wear the same old things

- And

hear the same old things that I do

"I

had hoped the States would be different for

me than England had been," Stevens explains

with a sad and knowing smile. "But things

are the same everywhere." "How Many

Times" was put on a shelf to collect

dust as Stevens turned his attentions to his

first appearance at New York’s.

Fillmore

East. This trip was only a scant eighteen

months after his recuperation from a collapsed

tubercular lung. During the months he had

spent in bed, Stevens had gotten into Yoga,

studied metaphysics, and had written a lot

of new songs that reflected his new, introspective

thinking. Incorporating the tunes into an

album called Mona Bone Jakon (a

title rumored to be about Cat’s affection

for his erect genital), Cat Stevens had started

on his way to international stardom.

Genital joy: Along

with success came a total lack of privacy

and never-ending stream of business obligations.

He was stopped on the streets for autographs

and was cornered in restaurants by loving

fans who wanted to snap his picture. The Cat

arched his back at the public’s intrusion

into his private world and reacted by spending

more time hidden away in his white London

house.

But

Mona Bone Jakon was

just the beginning. Tea for the Tillerman established

Cat as a melodic, moving artist extraordinaire

in the United States. And the next LP, Teaser

and the Firecat,

hurtled Cat Stevens into undeniable

supremacy as one of. The leading solo male

singers in the world. Not only did Teaser sell

into the millions, but it was swiftly made

into a children’s book with original

drawings by the singer. At the end of that

year Cat Stevens’ words had been translated

into eleven different languages, including

Japanese. Yet the limelight was pushing the

retiring young man further into seclusion.

For almost a year he refused all interviews

and shied away from any form of publicity.

Cool

spat in the heat:

It was in that year, 1972,

that Cat Stevens purchased a terraced house

on a quiet street off London’s North

End Street Market. It became a secluded oasis

on a desert that burned with the hot sun of

the public’s eye. First the Cat decorated

one floor like a discotheque:

"I

play records and entertain there. It’s

a great room for people who want to feel nice

and watch a fish tank or something."

On a higher floor Stevens designed what he

calls "My Little White Room." It

has the barren quality of a farmhouse. As

he describes it, "There’s no furniture,

one bed, and a bathroom." In the corner

stands an omnipresent symbol—a stark

white upright piano. It was in this room that

Foreigner would be written, but not

until Stevens’ next trip to the United

States had convinced him it was time to shake

up his sound. "I

play records and entertain there. It’s

a great room for people who want to feel nice

and watch a fish tank or something."

On a higher floor Stevens designed what he

calls "My Little White Room." It

has the barren quality of a farmhouse. As

he describes it, "There’s no furniture,

one bed, and a bathroom." In the corner

stands an omnipresent symbol—a stark

white upright piano. It was in this room that

Foreigner would be written, but not

until Stevens’ next trip to the United

States had convinced him it was time to shake

up his sound.

Catch

Bull at Four was released in the fall

of 1972, and Stevens was off to America for

a third grand tour. "I’d do an album,"

Stevens explained, "and then I’d

do a tour in September in the States. The

whole thing was becoming so obvious I felt

like I was becoming a puppet to myself and

other people."

The radio messiah: Halfway through the

thirty-city trans-American trek, Stevens knew

he was suffering from on-the-road blues. "I

wasn’t really enjoying going onstage

every night. I got very paranoid and started

to think I was drying up. I said, ‘What’s

wrong with me? This wasn’t the reason

I started."’ As the Cat Stevens

caravan criss-crossed the United States, the

Greek-Englishman started to think about why

he was writing and what he was writing about.

"I came to the conclusion I wrote because

I was in love—whether it was with a girl

or just with life. I realized that I’d

been writing about things that I’d never

experienced, things I’d only imagined."

It

was then that Stevens began to make his drastic

decision. On the road without a record player,

he found himself constantly listening to the

radio. "The best stuff I was listening

to at the time was black. It was during the

end of the September U.S. tour going from

Los Angeles to New York. Certain things caught

my ear. One thing I really got into was Stevie

Wonder."

Black bonfire:

Just before reaching New York the Cat took

a side trip to Miami to see an old friend

who was always turning him on to new music.

One night, with the tropical sun setting and

the palm trees waving in the wind, Stevens

heard an album by a Philadelphia soul group

called "The Blue Notes." "As

I listened to it, it all started to seep in.

Suddenly I realized that the whole of my musical

upbringing had been dealing with black music.

It was the stuff I had grown up on in England.

In the very beginning I went through the whole

blues thing—kind of like getting into

black music through the back door. Leadbelly

has always been one of my favorites. I realized

that most of the time I had been naturally

affected by black music."

His

career, however, had evolved from a strong

acoustic influence. "I had been pushed

into acoustic things like James Taylor, Carole

King, and Elton John. I took a look at the

white music and said, ‘I’m part

of all that.’ I felt kind of strange.

I turned around and I was a foreigner to myself.

I felt like that wasn’t me anymore. I

snapped out of it. I don’t want to go

on playing predictable me. I don’t want

to act me, I want to be me,

and I’m changing at the moment. If black

music was happening, I decided to just get

down to it. And because I was a stranger in

the world of black sounds, I called the album

Foreigner."

Inside

the Cat’s pajamas: A New

York concert at Philharmonic Hall was Stevens

last stop before returning to London and his

white composing quarters. He wanted Foreigner

to sound black musically, but lyrically

his songs were to be in much the same style

that he was already associated with.

Although

all of Foreigner can be considered

a masterpiece, the seven songs that comprise

the "Foreigner Suite" (which occupies

the entire first side of the album) are breathtakingly

brilliant. Oddly enough, the "Foreigner

Suite" begins with an announcement to

its listeners. Stevens was sitting in his

Little White Room trying to write an opening

song when he thought, "Here I am writing

words that will be heard by millions of peopie

and I realized how many various explanations

there were going to be of this song. So I

put a lecture in at the beginning."

There

are no words I can use There

are no words I can use - Because

the meaning still leaves for you to choose

- And

I couldn’t stand to let them be abused

- By

you, you, you

After

a delightful electric piano rag, the suite

swirls into an optimistic tune called "Sunny

Side of the Road."

- Dreams

I had last last night

- Make

me scared

- White

with fright

- Over

to that sunny side of the road

- Over

to that sunny side of the road.

"It’s

just my manner of being positive," Stevens

explained recently as he strode to the far

end of Island Records’ London office.

"Wherever you are, at any time, there

is something good about it. Most of the time

a lot of people go around being negative.

If everybody thought about good things instead

of bad, we’d be better off."

Graveyard

express: Though Stevens

tries to look at the happier side of things,

his bout with TB has left some strong feelings

about his own mortality. "The Hurt"

is a cut that sums up his feelings about death

and a constant search for happiness. "I

don’t think there’s anything that’s

going to make me happy. I’ve got money

and fame and a great career, but I’m

still not really happy." Is there a positive

side to not being happy? As far as Stevens

is concerned being positive doesn’t necessarily

mean you exist in a cloud of blissful euphoria.

"There’s no way you can go through

life without getting hurt," Cat says,

but pain can offer you an understanding of

why you are living in the first place:

- Until

I got hurt

- Until

I got hurt

- I

didn’t know what love as...

"I realize I’m heading straight for death

with no detour, and I want the moment of my

death to be as free as possible."

One

of the most sensational cuts on the album

is called "Later." Stevens explained

that he wrote it when he was feeling a little

horny, but the lyrics explain themselves.

- Later

- I

want to talk it out with you

- Try

to get my message through

- That’s

not all I want to do

- Later!

- I

want to feel your body close

- from

your head down to your toes

- Maybe

help you fold your clothes

- Later!

Key to the gilded cage: This

past winter, when The Foreigner’s

lyrics and basic melodies were composed

and ready for production, Cat Stevens made

the announcement that he was flying into the

Caribbean sunshine to record. Not only had

Stevens shocked the music world by dismissing

his long-time sidemen Alun Davies and Alan

James, but for the first time in three years

he was producing his own album. And that’s

when the soul sounds really set in.

If

Cat Stevens felt like a foreigner to black

music when he began this album, he certainly

must be considered a friendly neighbor now.

Soul music, however, may still be just another

passing phase in this remarkable performer’s

life. "I’m opening up more because

I want to listen to any kind of music. I don’t

want to say, ‘That’s not my bag.’

I’ll listen to anything. Free thought

in music has got to be the food for my freedom."

Top

of Page |