- Sounds Magazine

- December 13th 1975

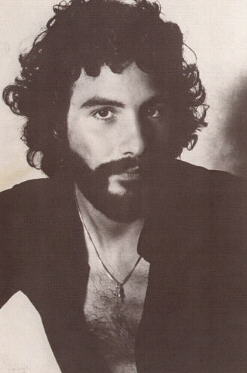

- Courtesty of Linda Crafar

Cat Stevens Talks To Mick Brown

It

was perhaps inevitable that Cat Stevens, of all people, should suffer the musicians'

equivalent of a mild seizure. All that earnest self - examination and revelation, burning

the emotional candle at both ends — for himself and his audience. And on top of that

the actual physical demands of being everybody’s favourite inner-self — album /

tour / album / tour / tour, to the point where the whole thing, becomes an exercise in

self-justification, which is really no justification at all. It

was perhaps inevitable that Cat Stevens, of all people, should suffer the musicians'

equivalent of a mild seizure. All that earnest self - examination and revelation, burning

the emotional candle at both ends — for himself and his audience. And on top of that

the actual physical demands of being everybody’s favourite inner-self — album /

tour / album / tour / tour, to the point where the whole thing, becomes an exercise in

self-justification, which is really no justification at all.

His albums mirrored the

impasse Stevens was rapidly falling into; moving inexorably from the sad-eyed, wistful,

love-sick romantic to the just-as-sad-eyed, wistful pilgrim, abandoning the search for

requited love in pursuit of Greater Things.

The strain of engaging in

a spiritual quest before an audience of millions would eventually have to tell — and

sure enough it did. Stevens, apparently in a state of mental confusion, retreated.

It is a distressing sign

of the nadir his career appeared to have reached that, to be truthful, one didn’t

actually realise he had gone until it was announced that he was back again — with a

new album and plans for an English tour, his first — it transpires in almost two

years.

I met Stevens at his

management office, a slick Mayfair number, where the mechanism for the up-coming tour is

being cranked into action — plans are being finalised, transatlantic telephone calls

made and flights booked.

Amidst this confusion you

notice that the office is something of a shrine to the man who makes it all possible.

There are artwork posters of Stevens’ albums on the wall, alongside awards from the

industry for this and that and a battered gold eight track cartridge For ‘Teaser And

The Firecat’ hanging by a piece of string. The gold records are in the other office

downstairs, literally covering the walls.

Stevens seems rather

embarrassed as he leads me into this room, and exclaims. Oh Christ, he shouldn’t have

brought me in here. Such are the preconceptions I have about the man, based on what I've

heard and surmised from his recorded output, that I immediately interpret this as the

remark of an aesthete, pained that a stranger should bear witness to the base material

rewards of his Art. Thinking about it, I decide he's just being every-day modest, and that

it's bad to have preconceptions.

We talk about the new

album. It is called 'Numbers’, subtitled 'A Pythagorean Theory Tale’. One

reviewer seizing on Phythagoras’ famed theory about the square of the hypotaneuse

asked whether this choice of theme meant that Stevens himself might be a right-angled

triangle?

Well, no. Pythagoras

probably learned his triangle theorem from the Egyptians; his main interest was the

mystical significance of numbers, a philosophy he developed from the relativity of notes

on the Greek musical scale. Stevens was introduced to the theory by a lady named Hestia

Lovejoy, to whom 'Numbers' is dedicated.

"She came to see me

when I was in Australia and started talking about numbers", Stevens explains.

"At first I couldn't see the point of making numbers any more important than what you

use them for. Then I read this book she'd left me on Pythagoras and realised that I’d

always known the importance of numbers without really being aware of it — like all

songs have a natural 'three’ element, three being the strongest number of all (hence

‘third time lucky’). Then you start finding out that Pythagoras developed the

Western musical scale. Then, thinking about it, you discover that the law of music is the

same law that applies to nature as a whole, that your life has octaves in .the same way as

the musical scale does. . ."

Then you go out and make

an album about it, which is, thankfully, less obtuse than the foregoing might suggest. If

you want to do it properly, the starting point for the album is the booklet that comes

with it, which sketches a Tolkienesque tale about an enchanted palace, peopled by nine

characters (Monad to Novim inclusive) who exist to give numbers to the universe.

A few of these characters

from the book crop up in the songs, but not all: and not all the songs are about

characters in the book. Some are Stevens being sad-eyed, wistful and philosophical, and

one 'Jzero', is a characterisation of the number 'Zero', which is analogous to the Tarot

card 'The Fool'.

Alternatively, you can

overlook all that stuff and just listen to the music, which, if you’re not in a

cerebral mood, is probably the best idea.

Musically, this is

probably Stevens’ most satisfying album since ‘Teaser And The Firecat' —

lots of clever melodies, arrangements that neatly complement Stevens’ exaggerated

staccato phrasing and an overall production, which is full without being over-bearing.

It’s an album which bears the mark of much work, expense and time.

"It took a long time

because I produced it", says Stevens. "It was the old thing that if you’ve

got two days to do something you'll take two days; if you’ve got three you’ll

take three. I didn’t have any time limit at all so we ended up taking four

months,"

The album was recorded in

Canada with string arrangements added in New York and mixing completed in Paris. Stevens

chose Canada because we had heard the studio had a big window overlooking a lake.

"I hate coming out of

a studio at night and you don’t know what you've missed. . "

He admits that he’s

happier with ‘Numbers’ than he has been with an album in a long time. The

respite from touring and recording has clearly done him good, restored some of the

equilibrium which his music — and perhaps he himself — seemed to be losing.

"I certainly reckon I

lost my way somewhere along the line", he says. "The whole thing was getting too

regimented — the need to make albums and do tours, not necessarily, because I wanted

to do 'em but because they had to be done. It was getting really silly. I was saying to

myself 'What is this?', because I’d forgotten what I was doing it for. And what I was

originally doing it for was to make myself happier, because basically I'm not all that

happy. I’m kind of one of these. . . solitary people…"

He looks wistful for a

moment. . .

"I’ve always

been like that, and I’m beginning to realise that that's the way l am and I can't

change that — I don’t think. I think I was meant to be like this, a bit more

solitary than . . just through circumstances."

He pauses. I am by now

growing accustomed to Stevens’ manner of talking; the fragmented sentences, a new

idea crowding out the old one before it’s been fully developed. Not so much a

presentation of thoughts as an unravelling. Anyway, he continues.

"That’s not the

point. The point is I was losing the line somewhere. And then I found it again; just as if

it was lying there, waiting for me to see it. . ."

He found it, he says, in

Brazil. Alone, cut off from the associate ideas. England, everything — with just the

music, the mountains and the sea. He says he knows it sounds like he’s trying to be

poetic, but that’s how it really was. It is necessary, he says, for any musician to

get back to the source of their original inspiration for making music before it’s

lost in the sheer mechanics of being 'a performer' and al that entails.

"It's like that club

they have in New York which is just for session musicians to go and have a jam.

That’s really important because if you begin to think that music is just being booked

into a session for three hours you're getting a totally wrong conception of what it's all

about. It’s easy to do that though. You get people coming up to you waving pieces of

paper, saying 'This is where you’ve got to be on such and such a date’, and you

start believing that that's the truth of the situation. It's difficult to keep

everything balanced. It can be done if you don’t block off your head to new ideas and

keep changing things around. It's basically what Mao said about communist society —

that it has to change every seven years or it becomes stagnant . . ."

Drawing on established

sources to illustrate or shore up his ideas is something else you become accustomed to

Stevens doing during a conversation. Mao, Carlos Casteneda, Paul Repps (author of the book

'Zen Flesh, Zen Bones’, which inspired Stevens' 'Catch Bull At Four’—

itself a Zen dictum) — Stevens obviously spends a lot of time reading and

assimilating philosophy.

When I ask him whether, in

view of what he has said about the danger of musicians losing their sense of direction, he

now feels that he personally has a clear sense of purpose, he paraphrases 'Desiderata':

"Everybody has a

right to be here — that's really all you have to know. Just understanding that you

are necessary to the universe or whatever — the scheme of things — that

fulfils my purpose. Even if l wasn't singing I’d be doing that." (It says

something for his conviction that Stevens makes it sound like a piece of wisdom chiselled

on a 15th century gravestone, rather than a piece of schlock, pushed out to corner the

Christmas market.)

Why then does he carry on

singing?

"Cos I like it more

than anything, it gives me more. . . not money, but everything else I need. Yeah, the

recognition is important. It gives me a reason for being there. If I didn’t have that

I'd have to find some other way of getting my fulfillment from people. I need that

feedback. We all do."

Money, he hastens to add,

is not important; a familiar cri de coeur of rock stars who are nailed to the floor

by the weight of greenbacks, but Stevens insists it’s true. It's true also that

he’s wealthy — enough to be a tax exile, (I did it quietly, he explains), to buy

land in Brazil, to build a house, and to facilitate his passion for travel. But as he

says, it's only as important as you make it.

"I can go first class

everywhere. But that isn't necessarily the best way of doing it, The best times I’ve

had have been when I’ve roughed it. I can have a limo waiting for me when I arrive at

an airport — but it’s better to get a taxi and have a conversation with the

driver. Money is the difference between two worlds: one is basically illusion, unreal.

It's made to look better, but in fact people are the only thing that really change your

life in important ways. Money hasn't ruled me. It's ruled by other people only because

they haven't had the advantage of being able to keep a hold on the other side, see what's

happening in the real world, and see themselves from both perspectives. I had that

chance when I was missing for a little while after 'Matthew And Son'. That illness was

perfect; it enabled me to see that the whole thing wasn’t real."

The illness was

tuberculosis and it checked Stevens career in mid-stride. He had had his first hit record,

'I Love My Dog' a year before, when he was 18.

As Steven Dimitri Georgiou

he had had an unusual childhood. The son of a Greek restaurant owner, growing up in the

closely-knit parochial Greek/Soho community — his main recollection is of loneliness.

Even before the halcyon days of hippiedom he was a drug coterie of one. All things were

available when you lived in Soho; we'd go to school stoned behind dark glasses, with

everybody wondering what the hell he was giggling about.

He was discovered in 1966,

renamed Cat Stevens and his first record, 'I Love My Dog', released. He appeared on

'Ready, Steady Go’ in the same week as the Troggs and Kim Fowley singing 'They're

Coming To Take Me Away'. He became a star. He remembers himself on the radio, for the

first time and realising that at that instant he was being heard all over the country. It

was, he says, the most incredible sense of power.

"It all went to my

head a bit. I wouldn't go out anywhere unless everything was laid on for me in advance:

everything had to be the best It started changing me, because I was too young to

cope with it. I suppose I should have been more aware, but I wasn't."

The ensuing lay-off after

‘Matthew And Son', gave Stevens breathing space to reflect on the changes success had

wrought in him. It obviously tempered his escalating ego, and when he re-emerged a year or

so later with 'Mona Bone Jakon' and then 'Tea For The Tillerman', a more acutely developed

awareness of self was evident in his music.

The lightweight, if

evocative observations of his first two hit singles had given way to more introspective,

carefully thought out ideas. Nothing profound, mind, but perceptive enough to strike a

sympathetic chord with enormous numbers of people, and establish Stevens as a kind of

pilot through the emotional chops and swells of life.

"I'm just a reflector

for other people," he says. "If I'm going through hassles people can see that

and say 'Right, well I can recognise that one, I won’t do that’. That's the role

I seem to play. I get a lot of letters and stuff from people — a lot of feedback

about what I'm writing. But I know that scene from when I was looking at the pop scene

from outside myself. I'd dream about certain people and it was like I knew them

personally. We all know each other basically through music — it's the fastest way

there is to get to know someone."

By the time of 'Buddha And

The Chocolate Box', however, it was apparent that Stevens development of ideas had led him

farther away from his audience, not closer to them; his reflections had become more highly

personalised, less obviously universal, and had begun to smack of evangelism.

"As you change your

ideas get finer", he says. "You get more oblique to the public, so they

don’t really know what you're doing. It gets to the point where do something thinking

it's a giant step forward whereas it's very minute in the picture of things."

Stevens had reached that

point, and it was his realisation that this was what was happening that made his retreat

to Brazil and the temporary lay-off from recording all the more timely. Certainly from his

audience's point of view it has been beneficial. It has meant that Stevens has

rediscovered the impulse for performing and is back on stage — something which seemed

unlikely to ever happen again I8 months ago, and his obvious delight to be touring and

recording again augers well for the future. He says he already has enough material to

record another album, and being on the road will probably bring forth more.

"I find I write more

when I'm moving. I need different impressions to feed me, and that comes a lot from

touring and just being with musicians all the time — not thinking about anything

else."

The new material, he says,

is likely to be less complex.

"The lyrics are

getting simpler perhaps. Things that I can sing and enjoy singing without worrying too

much about what the lyrics are saying. There's probably a danger of my audience thinking

my songs were getting too philosophical, but really I don't know how I can stop that

completely; that's me. It's the way I think, and it's the way it comes out. To stop it and

try something else would be even worse."

A lot of people make

out they're complicated. At least I'm honest — I am complicated…."

Top

of Page |