| Article

contributed by Linda Crafar

The Guardian 26

March 1998

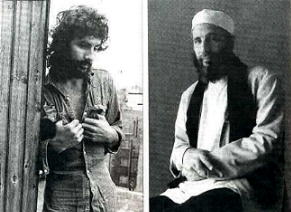

When Cat Stevens

turned to Allah, it wasn’t just his old name that he gave up. There was no place in

Yusuf Islam’s life for either music or humour. So what’s he doing with a new

record? And has he really lost the scowl? Simon Hattenstone reports.

The man on reception says

he doesn’t know if Yusuf will be coming today. I’m not sure what I’m doing

here — or where I am, for that matter, I think I’m meeting Yusuf Islam who used

to be Cat Stevens who used to be the little Greek Orthodox boy Steven Dimitri Georgiou

many, many years ago Our date has not been confirmed, though. This flat, featureless

building claims to be a hotel — London’s first Muslim-friendly hotel, according

to the brochure — but masquerades as an old age people’s home.

"Yusuf lslam sometimes

comes here," says the man on reception. "He pops in without telling us."

Oh, I say, confused, is

Yusuf a friend?

"Yusuf lslam, a

friend of mine? If only,"

Why "if only"?

"Well... Yusuf Islam

is a great man." He lowers his eyes.

Does he remember him as Cat

Stevens? Oh yes, he says, and he has listened to the old records in the past. But not now,

of course. Now he listens to Yusuf Islam’s new song, The Little Ones, a haunting

elegy for the dead children of Bosnia and Dunblane.

What does he prefer -

classic pop songs like Father And Son, Morning Has Broken and Moonshadow or the spartan

Yusuf of now?

"Oh, definitely now.

It has more... value — yes, that is the word. It’s not pop music, not

part of an industry it has a message."

If he didn't speak with

such awe, you’d think he’d been primed. I ask him how he knows Yusuf Islam, and

he tells me the great man is his boss, owns the hotel. "Look, look, that’s

him across the road."

"Salam, Salaaaaaaaam,

How are you doing? Salaaaaaaaam."

Bear hugs all round.

The slight man with the black briefcase and hennaed beard looks younger, less severe than

in the post '77, post-retirement, post-seeing-the-Islamic-light pictures I’ve seen.

He’s wearing black trousers, a grandfather shirt, collarless jacket. Trim the beard,

slip off the hat, add a few curly locks, a handful of bangles, and you could be face to

face with Cat.

But Cat Stevens died in

1977. He cancelled a world tour, told us he was dazed and confused by the platinum discs,

the fans, the venal business of music. He said he’d become a Muslim. Ta-ta, you

won’t be seeing me again on Top Of The Pops.

And we didn’t. The

press wondered aloud whether he’d gone potty like Peter Green and Syd Barrett before

him. Meanwhile, Yusuf Islam emerged, and the Muslim activist and patrician set to work. A

nice wife was found for him, and he settled down to half a dozen kids and began to badger

the authorities. We need Muslim schools, he said, Our children have nowhere to learn. And

he hectored and persuaded and bullied and bored anyone who’d hear him out.

The Government wasn’t

interested, Brent Council wasn’t interested, local journalists only gave him the time

of day because he used to be Cat Stevens. And when they discovered he considered music a

blasphemy (only Allah can shake the soul) and wouldn’t talk about his former life,

even they gave up on him. The young Yusuf Islam became a treasured battleaxe for the

Muslim community and a bit of laughing stock to the rest of the world— a humourless

dogmatist with fake exotic accent. He may have made himself as unattractive as possible to

stave off would-be admirers, but he got things done. The first school was opened in 1983.

Now there are four of them and the infants’ has been granted state aid.

"You've got to admit,

it’s some story," says Bobby, Yusuf’s PR machine, "the man who

disappears from music just like that, and then makes his first record for 20 years.

Woooowww! Everyone wants his story, but he wants to talk about serious things like

religion and Bosnia and education."

Yusuf Islam is the

executive producer of the album I Have No Cannons That Roar, on which he has written two

songs, one of which he sings. His voice is unchanged, but accompanied by a dulling drum

rather than the guitar — stringed instruments are outlawed in parts of the Muslim

community. The message of his songs is necessarily morose, but you can trace their lineage

back to Tea For The Tillerman—he is still singing about how to relate to an

incomprehensible world. The CD is dedicated to the former foreign minister of Bosnia whose

helicopter was shot down by a Serb rocket, and part of the profits will go to Bosnian

charities.

Do you mind if my daughter

Alix sits in on the interview? I ask Yusuf.

"Welcome," he

says. "I hope she’s not too bored."

And he smiles softly,

benignly. It’s distracting, almost the smile of an idiot savant Eventually I realise

it reminds me of Michael Crawford as Frank Spencer in Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em,

a sitcom that shared its prime with Cat Stevens.

He tells me how terrible it

is that Bosnia is being ignored, that the conspiracy of silence about the genocide has

allowed the ethnic cleansing to repeat itself in Kosovo, how astonishing it is that the

culture has survived unscathed. I’m listening, agreeing, and I can’t help

thinking how well the old cockney voice suits him.

I also can't help thinking

that, despite his sincerity there is another agenda. That, actually, he does want to talk

about music — music of the future and music of the past, as the terrible John Miles

song went. That Yusuf Islam wants to reclaim some of Cat’s baggage.

We talk about the old days.

I’ve been warned that he’ll skillfully reroute the conversation back to Islam,

but he doesn’t.

Where on earth did the name

Cat come from? It must have taken some crazed marketing genius to invent it.

"No", he says,

bashfully. "I did"

Why?

"There were all sorts

of influences, films like What’s New Pussycat?, Cat Balou ...Cats are beloved things

to people, and I wanted to become beloved. I wrote a song called I Never Wanted To Be A

Star, and it has a glimpse of truth. I just wanted a little bit of; you know, love."

Couldn't he get it from

family, friends, lovers?

"I don't know. I was

good at drawing, then it grew into music, and that appreciation….I suppose you just

want more of it."

The diffidence makes sense.

Cat Stevens never really enjoyed the pop game. Yes, he was Che Guevaraishly sexy, and wore

an open-necked denim shirt like no one else. Yes, he had stacks of money and a girlfriend,

the actress Patti D’Arbanville, who became the heroine of one of his songs and went

on have an affair with Miami Vice’s Don Johnson, not to mention a tattoo on her

bottom. But the real Cat Stevens was just a heaving soul of neuroses. The bedroom angst of

the records — pretty, melancholic songs about flowers, love, fathers, mothers, dying,

honesty, coping and not coping — was stamped in his heart.

"After the initial

success, I found myself a fantasy figure," he says. "My whole life became

exaggerated, and based on people’s idolisation. Unless you have experienced it, you

can’t understand how terrifying that is. I needed to talk about my fears and my

weaknesses, but despite the fact that I was surrounded by people all the time, there was

no one for me to talk to."

He thought he was cracking

up. Even the earliest cuttings talk about a man plagued by doubts, stammering and lisping

away towards embarrassed inconclusiveness. He worried he had nothing to say to anyone

because he’d said it all in his songs.

Did he like Cat Stevens?

"It was a name I had

to learn to live with, and I never quite, hee-hee-hee, managed it." He giggles like a

coy girl.

One day he ignored the

danger warnings and went for a swim in the sea. He found himself lurching further and

further into the depths. He found a prayer: if you save me, I will dedicate my life to

you, God. A wave flung him round and he managed to swim back to safety. Soon after, his

brother gave him a book about Islam.

Did he need to make such a

violent break from his former life? He says that it rejected him as much as he rejected

it.

"I cut myself off from

many people because they refused to understand. If you only like me because I am like you,

then what kind of friendship is that? If you like me for who I am, then you can still be

my friend. There were many breaks I had to make because people wouldn't accept me for who

I was."

Like so many converts, he

became inflexible, extremist. He wanted to follow the letter of the law to I prove that

even a former pop star could quote the Koran with the best of ‘em. He decided his

former philosophy — love can cure all —was na´ve.

"Justice has to have a

place before one can achieve peace and love."

He weaves an intricate

moral maze with the concepts of justice, mercy, peace and love as Alix walks over to him

with a picture of a man wearing a hat not unlike his own. "Oh, that's

lovely...Why’s he wearing a flowerpot on his head?"

He regards Rushdie as a

criminal, said he should be sent to Iran for his just deserts.

Does he feel the author of

Satanic Verses is deserving of mercy?

"I don’t want to

talk about that"

But it’s important, I

say. Should he be allowed to live?

"Again, this is one of

those things that once mentioned, becomes a headline... My views were

misrepresented."

How?

"Again, I don’t

really want to get into this. I think we should move on"

Why?

"Because it might

focus people on it."

So we should forget the

fatwah?

"It distorts Islam,

its precepts, its conditions, its values. Law itself has so many aspects it cannot be

narrowed down, Oh, Aliix, that’s very interesting"

She’s drawn a pair of

flags.

"Wow, look — two

opposites, Opposites mean they are on different sides... but the wind is blowing the same

way."

She walks back to her

little desk happy. His language may sound tortuous and obfuscatory, but on its own terms

he is treading a new path every bit as radical as when he suddenly announced he was Cat

Stevens and then Yusuf Islam. He does not seem interested in condemning and dividing these

days. But he’s in a tricky position. He can’t be seen to be too critical of old

friends — the traditionalists or fundamentalists, call them what you will —who

remind us at every opportunity that Rushdie should be dead.

I mention that he seems

more at peace with himself these days, more willing to embrace the paradoxes.

"I think I've had the

time and space to look at what I’m doing, and today I suppose what I represent is

British Muslim. I came to Islam after an extraordinary journey and in the end I had to

discover a balance between who I am and the image — the things I stand for."

The war in Bosnia and his

visit there helped bring about the transformation.

"You look at Bosnians

and they’re all white, most of them blond Muslims from Europe, and they sit

comfortably in their own surroundings."

He no longer blushes with

dismay and anger at the life of Cat Stevens. He accepts it as a valid part of his life,

his growth.

"It is the backdrop to

who I am today."

Does he ever sing the old

songs in the bath while scrubbing up for prayers?

"More than I used to.

I’ve been revisiting songs from out of the archives because they want to release some

unreleased material. So yeah, occasionally I find myself thinking about it - more thinking

than singing."

Some of the songs still

move him, and he screws up his eyes to quote from distant memory.

"Let me think. Well,

there were sentiments like, like...

If-I-ever-lose-my-eyes-uhm-If-I-ever-lose-my-eyes-I-won’t-have-to-cry"

It’s difficult to

recognise when he quotes in monotone, but I sing anyway. His eyes light up and he smiles

the Frank Spencer smile.

"That’s it,

yeah—Moonshadow."

I tell him he seems

desperate to be involved in music again.

"It’s not just

music, it’s a matter of balance."

Is music really wrong? The

point I’m trying to make is that culture, something quite natural, is a part of life.

"I may be criticised

by some elements within the Muslim community but I feel confident enough to know that at

certain times in certain places you do something to provide for the needs of the people.

That’s why I went into schools. Now I’m moving past that to a cultural need,

especially for an identification of something good with Islam."

What if he found himself in

the charts again?

"Embarrassing" he

whispers.

Why?

"This kind of music is

for a selective audience. I’m not sure whether it would sell in large numbers. Today,

a lot of it is hype, and this is nothing to do with the hype, it’s the real

cause."

But there are millions who

believe in the cause.

"Well, who knows what

may happen. But it’s not what we’re after... Oh, Alix, those suns are lovely.

But why are the clouds crying?"

Because they don’t

want to rain, she tells her new friend. And they walk off together.

|