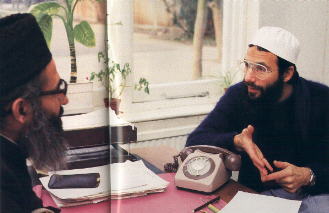

His black beard is

bushier. His locks, once long and tousled, are now cut to medium length and parted neatly

in the middle. He wears glasses today, but the eyes still sparkle, and he’s garbed in

a white, ankle-length robe.

He is Yusuf Islam. Once he

was Cat Stevens, the British singer-songwriter superstar who charmed millions with such

ballads as "Morning Has Broken," "Peace Train" and "Father and

Son." Last spring, with sunshine and children’s voices streaming in through the

window, we talked in the headmaster’s office in a mock-Tudor house that is now a

primary school in the North London borough of Brent.

The Islamia Primary School

is Yusuf Islam’s brainchild. He’s provided much of the financing for it through

the Islamic Circle Organization (ICO), a charity he helped found. And, in a sense,

it’s what he discovered down that long "road to find out" that took him,

finally, to the religion of Islam.

The little school, which

draws 85 four- to eight-year-old boys and girls from Brent and nearby boroughs, is special

for another reason: It is bidding — much against the odds — to become the first

Muslim school in Britain to receive government funding, putting it on an equal footing

with Roman Catholic, Anglican and Jewish schools that have long received state money for

salaries and maintenance.

Long-awaited government

approval of the application for "voluntary aided status" would make the school

"the first in the whole of Britain — and one of the first in the whole of Europe

— to get government aid where a state can fund a religion" other than those

historically its own, says Arthur Steel, a Conservative-Party councilor who helped Yusuf

Islam push the aid application through the Brent Borough Council last April. Approval

would also set a precedent for state help to schools for the children of England’s

1.4 million Muslims, who form the country’s largest minority religion.

To qualify for government

aid, the Islamia School must be recognized as serving a community need, and its curriculum

and its classroom building must meet government standards. With state funding, Islam says,

the money now being spent at the Islamia School could be channeled to help another Muslim

school in East London.

Parents say government aid

for the school is "long overdue," arguing that their tax money should be

available for their own children’s education as well as that of Christian and Jewish

children. "It’s about time they gave us our rights," says Samir al-Atar, an

Egyptian whose two children attend the school. Adds New York-born ‘Abd Allah

Trevathan, who teaches at the Islamia School and has a son there, "Most Muslims pay

taxes that go to the borough. Why shouldn’t they get some of the money back?"

To achieve voluntary-aided status, a new building must be erected near

the present structure and the school’s enrollment boosted to 175 children up to age

11. Of course, more teachers would have to be hired to swell the current 10-person

full-and part-time staff. Finding the extra children would be no problem: there are

already 560 youngsters on a waiting list.

Early this year, however,

school officials were blocked in their efforts to erect the new building when the Borough

Council, controlled by the Labour Party since May 1986, refused planning permission for

it. Now, while appealing to the Conservative national government’s Environment

Secretary and looking into other options, "we must wait even longer," says

spokesman Ibrahim Hewitt. The aid program’s cost to the local Brent government —

if approved — would be some 250,000 pounds a year — about $400,000 — and

the national government would pick up the tab for 85 percent of capital expenditure. In

the meantime, the Islamia School encourages parents to contribute as much as they can

toward the education of their children. But only about 15 percent of the school’s

100,000-pound ($160,000) annual budget comes from pupils’ families. The ICO, to which

Yusuf Islam admits he is "the largest contributor," pays the rest.

Muslims come mainly from

that 20 percent of Brent’s 280,000-person population that is Asian, according to

Steel. He backs the funding proposal, since approval would enable the Islamia School to

enroll more children, reducing the need for new borough-built facilities. But Steel also

agrees philosophically with what the school stands for. "It’s better that people

have schools in which they can retain their own cultures and, more important, in which

they can learn the moral values of their own religions," he says. "That

won’t be taught in a state school."

Islam, who attended many a

Council meeting to lobby for aid, made it clear from the beginning that "money was

not the problem," says Steel. "It was acceptance lof funding for a Muslim school

that was the thing. He was more interested in the principle: that it be accepted as a

state aided school on a par with the others."

The Conservative councilor,

51, says-the name Cat Stevens didn’t mean anything to him when he was told of

Islam’s earlier identity — until someone sang him a few bars of "Morning

Has Broken." " I quite like that one," he says.

To be sure, Yusuf Islam has

come a long way — from capturing the hearts of young people around the world, to

making the case for a primary school in Borough Council chambers a decade and a half

later.

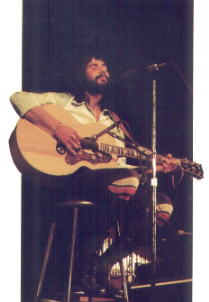

As Cat Sevens, he performed

with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Engelbert Humperdinck in Europe in the late

1960’s, and triumphantly toured coast-to-coast in the United States and worldwide in

the seventies. He even set up a tax-haven residence in Brazil for a time, but donated

liberally to charities and organizations, including UNESCO, even then. He reeled off eight

straight 500,000-selling "gold" records. His popularity was unquestioned.

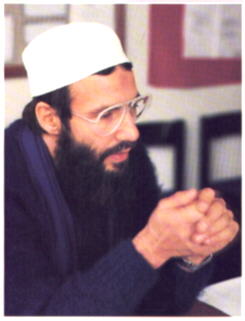

Now, soft-spoken, intense

and a devout Muslim, Yusuf Islam is light years away from his past. But he’s

unchanged in important ways, too.

He embraced Islam in 1977

and is now a leading member of a community of Muslims in London, the city where he was

born Steven Georgiou and schooled as a Roman Catholic, and where he got his start in music

in his teens.

At 39, he devotes himself

to the work of the ICO, which he founded with friends from the United Kingdom and Saudi

Arabia in 1982, and to the Jslamia School. He also chairs the London-based Muslim Aid

organization. In that capacity, he’s traveled to Sudan, Pakistan and Bangladesh on

refugee-relief missions, and met Afghan refugee children arriving in Britain for treatment

of their war injuries.

He’s been called

"a Muslim Bob Geldof," after the lead singer of the Boom-town Rats whose series

of aid concerts recently raised millions of dollars for drought-hit Africans.

But the school is the apple

of his eye.

Yusuf Islam’s interest

in children goes back a long way. There is ample evidence of it in the lyrics of his most

popular songs, and in the handful of interviews he gave at the apex of his career.

Notably, two of those rare interviews were with a U.S. publication for students, Senior

Scholastic. He also wrote — and illustrated — a book for children, called Teaser

and the Firecat after one of his top-selling albums.

"I’ve

seen youth lost, I’ve watched my,elf grow, and seen my attitude to children

:change," he told Rolling Stone in a 1974 interview that provided a hint of his

direction. "One must always change; that’s what children do. I find a lot of

people take their kids for granted. I still enjoy kids on the street, and there’s a

school across the back that I’m looking forward to visiting."

"I’ve

seen youth lost, I’ve watched my,elf grow, and seen my attitude to children

:change," he told Rolling Stone in a 1974 interview that provided a hint of his

direction. "One must always change; that’s what children do. I find a lot of

people take their kids for granted. I still enjoy kids on the street, and there’s a

school across the back that I’m looking forward to visiting."

Though Islam long ago put

away the guitar that set the tone for his thoughtful, sensitive songs, and auctioned off

all his gold records for charity, he says he’s still making music. Now, it’s

poetry, written and taped especially for children.

He describes his first

recording, "A is for Allah," as "a sort of singing, but without

instrumentation." The tape, in which Islam explains in English a number of Arabic

words important to the faith, is almost as popular as his earlier records. "It’s

being distributed today, and copied, and it’s all over the Muslim world," he

says.

The former star has kept

his lilting voice and joyful sense of rhythm, and the "singing" brings smiles of

recognition to old Cat Stevens fans. He says he’s considered making a new album, with

receipts to be donated to Afghan refugees, but adds that the plan is only in the

"thought stage"

"Music is anything

which will involve goodness in a person," says the man whom the Los Angeles Times

once lauded in a concert review as "an exceptional singer and artist. . . [able] to

combine strength, fragility and sometimes mystery in his highly personal

compositions."

Today, he describes his

music of the sixties and seventies as "kind of feelings in the dark." He says he

chose the title "Footsteps in the the Dark" for his last album —released in

1984 and composed of songs he wrote before he embraced Islam — because it documented

a period when "I was walking somewhere but I din’t know where."

"A long time ago I

started my quest for peace and enlightenment," Islam wrote for the jacket of the

album. "My soul was thirsty for the truth. My songs became a vehicle for my spiritual

search,.., but that still didn’t satisfy me." When he discovered Islam, "it

was as if someone, somewhere, had switched on the lights."

His first encounter with

Islam was in the suq in Marrakesh, Morocco, where he’d gone to gain inspiration and

write in 1972.

"I

heard singing," he recalls, "and I’ll never forget: I asked, ‘What

kind of music is that?’ and they told me, ‘That’s music from God.’

I’d never heard that. Music [had been] for praise, for applause, for people —

but this was music seeking no reward. What a wonderful statement."

"I

heard singing," he recalls, "and I’ll never forget: I asked, ‘What

kind of music is that?’ and they told me, ‘That’s music from God.’

I’d never heard that. Music [had been] for praise, for applause, for people —

but this was music seeking no reward. What a wonderful statement."

He impressed the

Marrakshis, too. Shop owners in the wool suq would recount his stay to anyone willing to

listen long after he’d left for home. Yusuf Islam’s true introduction to the

faith came in 1976 when his brother, who had just returned from Jerusalem, gave him a

Koran as a gift. He started to visit a mosque m London, walking through the door not as

Cat Stevens the singer, but anonymously. Some of the men he’s closest to today still

remember the surprise they felt when they learned their friend was a world-renowned

musician.

"Yusuf, I never knew

you were a singer," one told Islam when he found out.

"You never asked

me," Islam replied.

He continued to write

music, sing and perform into 1977. But he was changing.

"I’d reached the

peak of my success and was riding the wave, but I was carrying the Koran everywhere with

me," he recalls. "It was the most important part of my belongings. The Koran

contained, for me, the complete universal guidance for human beings. Before that time I

didn’t believe there was any religion I would submit to or commit to.

"Show business is not

conducive to a life of service. Either I was to go fully my own way making music and just

pleasing my own desires, or I was to submit myself fully to Islam."

He chose the latter,

praying and fasting, gradually withdrawing from the music world and letting his contracts

lapse. And he chose the names Yusuf (or Joseph, the prophet) and Islam ("submission

to the will of God") as a statement of his faith.

The Islamia School quickly

grew out of that faith — and out of his family.

The facility opened in 1982

as a "play group," or nursery school, with 13 youngsters, the children of Muslim

friends, and Islam’s own two oldest daughters, Hassanah and Asma.

"The necessity of the

school came with the birth of my first child [in 1980]," Islam says. His entry into

education was spurred by a disenchantment with the schooling offered by

"experts" who "were ignorant of the facts."

The Islamia School’s

objective? "In one word, paradise," he says. "The basis of Islamic

education is to guide a person in his own life to believe in accordance with the divine

will, with God Almighty." The Islamia School aims at educating a child "in all

aspects of his life and personality, including his spiritual, emotional, mental and

physical development."

Ultimately, the Islamia

School would like to open a secondary school for children 11 to 18, with separate

facilities for girls and boys, says Islamia headmaster Azam Baig, a Pakistani.

"It’s better for kids to continue here than to go to a school where the

atmosphere is altogether different. We won’t finish, God willing, until we have a

secondary school."

The primary school children

bring with them a rainbow of backgrounds from 23 different nationalities, offering each

other a rich learning environment before they ever open a book. Their parents hail from

countries including Zimbabwe and South Africa, Morocco, Iraq, Egypt and Libya, Jamaica,

Malaysia and Mauritius, and the United States and Britain.

Youngsters retain many

facets of their own culture in the schoolrooms. A cheerful boy coifed in Caribbean

dreadlocks provides a colorful contrast as he does his lessons a seat away from a dainty

little girl from Egypt who wears a head covering and a long dress.

The school offers the same

syllabus as English state schools, with one key difference: Along with science, geography,

English and mathematics, there are classes in Arabic, the Koran and Islam. The

school’s own imam, a graduate of Cairo’s ancient al-Azhar University, teaches in

the musalla — a prayer room with a mat-covered floor —and the boys and staff

attend Friday prayers at one of two local mosques.

Farouq Hassanjee from

Mauritius put it simply when he stopped one afternoon to pick up his six-year-old

daughter, Shehnaaz. He called Yusuf Islam "the patron of the school," adding

that the facility "makes the general raising of children easier" by providing an

Islamic education during the day instead of only after-hours.

Islam comes to the school

every morning, to help out with sports activities and academic and administrative matters.

Notes headmaster Baig, "Yusuf is totally devoted and this is his mission. He has a

God-given gift and he’s using it. Yusuf is lucky."

Consciously or not, Islam

has answered the question he posed some 15 years ago in "Where Do the Children

Play," a song in his album Tea for the Tillerman. In it, he asks:

Well

you've cracked the sky,

Well

you've cracked the sky,

Scrapers fill the air,

But will you keep on

building higher,

Till there's no room up

there?

I know we've come a

long way,

We're changing every

day.

But tell me, where do

the children play?

That’s easy to see in

Brent. They’re playing, and learning, at a little Muslim primary school built by the

man whom many of another generation still fondly remember as Cat Stevens. ~

Arthur Clark

has lived in Ireland and Morocco, and is now an Aramco staff writer in Dhahran.