This is a French article translated into English for Majicat.The

magazine was called 'Rock and Folk' from February 1976. This article

comes courtesy of Jennifer Perez, and once again a big thank you

to Michael Valenzuela for translating this wonderful article for

us into English.

~Cat~

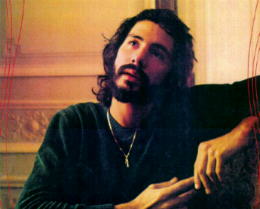

Boy in the Wind

Does Cat Steven's audience

like rock? Does the rock audience like Cat Stevens? If the answer is no, then this article

has nothing to do here.

A wisp of voice rises,

softly suspended by the lost notes of a grand piano. And it's just as well that with the

Palais du Sport crammed full like no one has seen before, the crowd respects a strange

silence, identical to what distinguishes a classical concert. Tossed among the human

waves, it is difficult to catch sight of the scene other than by flashes; meanwhile,

gliding among the clusters of girls who all look like they're in a state of celestial

bliss. One catches a glimpse of a fragile young man perched on a white platform advancing

toward the audience: Cat Stevens.

Scanning the eyes of the

audience, one quickly realizes that you're not dealing with the kind of crowd that makes

up the Parisian rock concerts. In the eyes of rock fans elsewhere, Cat Stevens is

definitely discredited. Since a sad thing called "Lady D'Arbanville", and the

album "Tea for the Tillerman", he seemed like an artist of international

popularity where the songs scarcely made up nothing more than music of mass consumption.

One album follows another, Stevens doesn't care. He has his own audience that reveres him:

high school students, a little awkward, who stare without being able to remove their gaze

from him. An audience, a bit anonymous, who scarcely love rock music and all the harshness

and violence it carries with it, but who seem to look for something else....maybe

tenderness.

Cat Stevens is on a

European tour which hasn't happened for many months. Last year the man had even entirely

disappeared. For reasons that pushed him to return, Cat Stevens explains further. The

worry of not plunging into oblivion as with a very keen sense of business partially

justifies this multi-millionaire's coming out of retirement. A new album is published

throughout the world ("Numbers") which he needs to promote. Professionalism.

The concert is divided into

two parts, the first being dedicated primarily to "Numbers", and the second to

"oldies". When Cat Stevens sings, it's the mass. When he stops, it's a frenzy.

The audience "plebiscites" the songs it knows best (the hits) and replies in

chorus with the singer and orchestra. And the fourteen or fifteen year old girl who shouts

in front of me makes me think of Marylou, with her braids and her cheap jewelry. How long

has she dreamed of this concert, leafing through her magazines alone in her room? The

following day, Cat Stevens opened his door to "Rock & Folk" for an exclusive

interview.

Hidden side

Benoit Feller: You retired

from the scene for a year. Why?

Cat Stevens: For reasons a

bit similar to what drives many others to act in this way in this business: I was tired. I

had enough. Not physically, but mentally: always the same life, the same tours, the same

circuits, the same people, the same universe. A break was absolutely necessary. Then I

left for Brazil, a country I already knew. I rented a house, clinging between the

mountains and the sea, and for three months I wrote my new album. Peace and tranquillity

were necessary for me, I found them there. I began to feel much better. As a result, I

went to Quebec to record what I had conceived, another three months in an incredible

studio, endowed with a view of one of the most beautiful lakes I've ever seen. While I was

at it, I devoted the following three months to mixing the ensemble, and the last three

months to designing the record sleeve and to putting the finishing touches to my work. I

took my time. Then here I am on a European tour to promote the album. And don't you

believe that I'm bored, that it's just a simple operation of marketing. The tours, that's

life, the people, I love that. But not for a length of time.

BF - This need that you

felt to retire, does it correspond to a profound weariness of your own music? To a need to

sing something else, to slip into new tracks? Your album "Numbers" is more

elaborate than the preceding ones, and especially the backing group that accompanies you

has never been present before, nor so expanded.

CS - Musical and human

evolution goes in pairs. I'm not telling you anything new in saying that Brazil is the

country of rhythm. Of rhythms. I spent that year away to listen to different types of

South American music. Some specialists except a few Europeans know the treasure of

Brazilian music, its wealth, its productivity. Slowly I assimilated what I heard. I also

like traditional Spanish music. And, while I was at it, I was introduced to the drum kit.

Today I have one at my house, in the same room as the stereo, and I play it as much as I

can. Maybe I'll have the instrument on my next record. It was an extraordinary discovery

for me, as if I'm expressing a whole new side which till now was hidden from my

personality, an unknown aspect of my being which remained inhibited. I felt an energy that

came from afar and slowly brought back from the depths where it was buried. On a total

other level, what happened to me is happening to rock today: the fascination with rhythms,

from another culture: Africa, the Antilles, the Third World. All you have to do is listen

to the work of Carlos Santana and his group, to consider what has been the enormous

success in the South American countries. And not just musically. The West ought to learn

from the Third World. The rhythms are like the pulse of blood. The music will always

reflect human movements, in the largest sense of the word. And that's what's about to

happen: the Third World is coming. Thus, I no longer write ballads in the style of

"Morning Has Broken" or " Father and Son", even if, like yesterday

evening, I still sing them in concert. These pieces, imbued with a simple and sad beauty,

remain for me the reminders of a past time, a troubled time, the representation of a very

hard ordeal that I had to pass. They're like old photos. I can play them because they make

up a part of myself, but to compose titles of the same vein would not make sense, because

I've evolved. And, in that sense, the year I spent away from the public, far from the

music world, had been very profitable. For it was precisely for the repertoire that I was

there. It costs me to have to present forever the same image which for example portrayed

the album "Tea for the Tillerman" or the song "My Lady D'Arbanville".

The solitude of Brazil shed light on my ideas, which made obvious a hidden conflict that I

suppressed but that made me eliminate it at all costs. I know that the audience is always

attached to the original Father and Son", even if, like yesterday

evening, I still sing them in concert. These pieces, imbued with a simple and sad beauty,

remain for me the reminders of a past time, a troubled time, the representation of a very

hard ordeal that I had to pass. They're like old photos. I can play them because they make

up a part of myself, but to compose titles of the same vein would not make sense, because

I've evolved. And, in that sense, the year I spent away from the public, far from the

music world, had been very profitable. For it was precisely for the repertoire that I was

there. It costs me to have to present forever the same image which for example portrayed

the album "Tea for the Tillerman" or the song "My Lady D'Arbanville".

The solitude of Brazil shed light on my ideas, which made obvious a hidden conflict that I

suppressed but that made me eliminate it at all costs. I know that the audience is always

attached to the original

image to the name of which

it loves an artist. But in this case, my audience must accept my evolution. It's why

"Numbers" differs greatly from my previous creations. The sound is new, and

especially the influence isn't the same. And I am the producer, which makes up a

considerable innovation. It is even possible that in certain places, I did too much!

BF - You mean to say that

your superstar status was for you a source of blockage, that it prevented you from

creating?

CS - Exactly. I didn't want

to work any more before feeling in me a new vigor, a new influx. I learned in time that I

was turning myself slowly into a computer, that I would go into the studio with the

enthusiasm of an employee who goes each morning to shut himself in a bank. A painful

observation, but one I had to admit. Symbolically, I cut my hair when I left. I wanted for

my twenty-sixth birthday the veil to be lifted. It was like a new birth; after some

months, the fire returned. But, at the same time, I realized that it had never left me, in

fact, that I had only forgotten how to let it talk in me.

BF- What do you resent when

you think back to the years before the break?

CS - I told you: I have the

feeling of looking at an old photo. I think that I reached a point where the energy was

completely lacking for me. Or, to create, one must feel pushed, almost badgered, run

through with a quasi-electric current. I don't regret anything. I've had my ups and downs.

I will go further; a depression was essential to perpetuate a certain understanding with

myself. And everything is clarified today. I am happier.

Numbers

BF - The words of your

songs seem to take on an importance with you that aren't generally there in the eyes of

many other artists. But does your audience hear them?

CS - I tell stories like

the balladeers of the Middle Ages who went from town to town and sang in the public

squares of the village. The comparison can seem na´ve, but I believe that it's justified.

I also believe that therein lies the profound reason of my success. You must TOUCH people.

Beyond that, everything in this business is trivial, for me at least. You're right, the

words I write are absolutely of major importance for me, and it's for that that I always

see to it that they are written on the sleeves of the records. To know if the audience is

paying attention or not is not a simple question. I think that few people disassociate

words and music completely; when you listen and re-listen to an album, you are immersed in

the ensemble. Words and melody bathe your head and they leave an imprint in a common

osmosis. One is hooked or not by the charm which emanates from the record entirely so much

as that. In any case, it is according to this conviction that I conceived Numbers. So

you'll understand better, I'll tell you this story.

In Australia I met a woman,

Hestia Lovejoy. Hestia is around 60 years old, and, as you can read on the sleeve of the

"Numbers" album, it is dedicated to her. I was very lucky to make her

acquaintance. She spoke to me of Pythagoras, of numbers and of their secrets. I was always

fascinated by numbers. It was a passion that was up to then latent in me and Hestia

awakened it suddenly. I wanted to find the meaning of figures and other symbols. Recalled

abruptly, these last ones don't mean anything, if it's not a simple abstraction. But in

reality, they make up the key to everything. They are the absolute law of nature. For

example, why is a week made up of 7 days, and a year 12 months? When I began to study the

question, I discovered that it is impossible to find a work of Pythagoras and also

practically uneasy to obtain books about him. Because Pythagoras was assassinated, and

after his death they burned his notes, all his papers, they tried to erase his name and

works from the collective memory. Because he was a revolutionary creature. Then I learned,

learned and learned again, and it is then that I wrote the story of which I made the book

that appears in the sleeve of the record. You can proceed with different lectures, and

there in lies maybe the most passionate aspect of the matter. Those who don't have a

mathematical spirit can see there in a dadaist or surrealist attempt.

BF - Aren't you afraid that

your audience would not be interested in all that? After all, these are only theories, as

the sub-title of the album indicates, "A Pythagorean Theory Tale".

CS - I don't know anything

about that. Frankly, I never thought about it. I let the subject develop in my head, then

I realized my album as it seemed good to me, with the sole intention of translating what I

was feeling. I think I have achieved it. Will they like this record? I am unaware of it,

but I am not afraid: for me, "Numbers" has its own charm, its own personality.

BF - How do you explain

your immense popularity? Do you excite the crowds everywhere like you did last night, at

the Palais des Sports, which, in passing, I have rarely seen so full?

CS - I don't know really.

When you are far away, when you remain absent for a long time, the people put a lot of

themselves into you, they desire you with a growing force. There, it's been some years

since I sang in Paris, and the reaction would certainly not have been so violent if the

audience had heard me here a month ago. I was deeply touched. Especially since the show

started badly; in the course of the three first pieces, we were having serious sound

problems, and we did not know if we could fix them. The balance remained disastrous

throughout the concert and the sound bad. I was worried and on edge. I don't know a more

enthusiastic audience than the French, when they are WITH you. There was a great

communication last night, a true human contact. Isn't that most important? That happens in

one out of ten concerts. In Germany, for example, the vibrations were very harsh, and I

had a big evil to "win over". But the Germans are very strange. When I don't

manage to establish a real contact, I close up, I become withdrawn. I hate that. No doubt

it's about fear, or shyness, of these uncontrollable reactions which engender the feeling

of being attacked.

BF - Do you consider your

musicians to be simple performers, or do you let them take an active and real part in the

development of your music?

CS - My musicians

participate up to a certain point. Chico (Batera), when he came to Quebec to record,

watched me work during several days, and suddenly told me, "You are an

architect." He was right. I conceive the ensemble, I direct it, I impose a structure.

This proves essential if you don't want to sink into shapeless jams. And the contribution

which belongs to each one, the personality that he expresses blossoms even more once the

setting is defined. Few musicians are capable of being leaders, most among them need at

all costs that said leader bring them to express the best of themselves. That's what I try

to do. And if I act in this way, it's because I remain persuaded that the color brought by

the group ensemble is fundamental in my albums. But a group deprived of its leader is like

a hydra without a head.

BF - You spent a lot of

time writing, reflecting. Do you intend to publish a book, or shoot a film?

CS - It's very possible.

Again, I'd have to discover the appropriate media. On reflection, I think it might be a

film. But what kind of film? A cartoon, a fictional story of the same type as

"Numbers", science fiction, realism? I need a solid frame, a stronger direction.

It's not a simple question of work.

Interview by Benoit Feller. |