| From Sounds December 9th 1972

courtesy of Chris Abrams

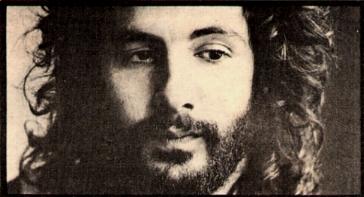

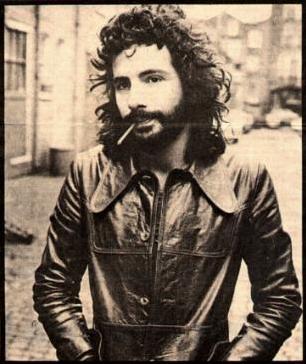

Penny Valentine takes a jaunt to see Cat Stevens

There's something a bit sad

and neglected about English seaside towns out of season. Once the buckets and spades and

the few rays of sun have been chastened away by the bite of those northern winds, they are

after all - just towns stripped of their bunting. But then maybe that’s when they

settle down.

Once the sightseers and

intruders go back home everything goes back to normal, and the Bed and Breakfast signs

left creaking in the wind are maybe not cleaned up again until early Spring.

Bournemouth - 70 miles

along the motorway from London - huddles into itself on Wednesday night as high winds and

torrential rain pound at it incessantly. It's raining so fiercely that the Christmas

lights in the town centre are a coloured blur.

Bournemouth is a kind of

middle class seaside town. Not as rich as Brighton, not as overloaded with toffee apples

and candyfloss as Blackpool.

The people who pack the

Winter Gardens are very enthusiastic but not over demonstrative. They've come out to see

Cat Stevens on a really filthy night and it's enough to prove their devotion and

admiration that they did it. But then that's the kind of artist Stevens is - drawing

people to him like a magnet when he's certainly not a rabid rock and roller in the true

sense of the word, and certainly never comes up with any tricks to get the audience off on

him.

Stevens' standing right now

is really huge. I know some people who, not being able to get a smell of a ticket for the

Royal Albert Hall, took to their wheels to go to Bournemouth without a moment's

hesitation.

Scared

By the end of Wednesday's

show - just 90 minutes after Cat walked on stage - the audience are up on their feet and

down at the front for "Lady D'Arbanville", singing along too - but it's taken

Cat quite a lot of talking to get it:

"It's funny - they

were loving it but they seemed scared to move," he says later sitting coolly on an

amplifier backstage. "I have to do a lot of rambling. It doesn't matter what rubbish

I say it's just that all that talking makes them realise something. That you're really

human".

These British dates are the

rounding off of four months on the road - Cat Stevens World Tour. And everybody in the

Stevens entourage tonight, aside from Alun Davies, Gerry Conway and the others, are

wearing T. shirts that give you an indication of just how long they've all been out on the

road.

There's been Australia and

Japan and America before this lot, and yet tonight it's very obvious that something's up.

That instead of an enormous feeling of exhaustion and sheer ploughing weight of so many

live gigs, so many miles, there's an incredibly high energy level with everyone.

Most of it is emulating

from Stevens himself. Everyone remarks on it backstage, but if you hadn't noticed it

anyway you'd be pretty dumb. He's really exuberant and happy - joking, laughing, ribbing

Conway, and singing "Dat little black dawg" with Jean Rousell in a send-up of

Alun's song . .

With only ten minutes

before he's due on stage there's none of the tension you normally get - not just from

Stevens, but from any artist that is noticeably jumpy before those first couple of early

numbers are tucked under their belt and they've had time to gauge what the audience is all

about.

But there's just smiles and

kisses and let's do the interview now', - which is really odd because it's the unwritten

law of rock and roll that nobody does interviews before they go on - and any journalist

who asks is a fool who just doesn't know what it's all about.

But he really does want to

talk - urgently - he requires to explain this new found emotional peak he's going through.

Why this inexplicable resurgence of energy should suddenly have hit him, three years alter

he came back to grow into the giant stature he's at now.

Success is probably the

most sought after, most prayed for and certainly most admired quality in the twentieth

century. Western life is built, packaged and ribboned around success. Success is not just

the American dream anymore - it's everyone's dream. To the artist it appears to bring its

own rewards.

Strength

But like everything pretty

and shiny and smelling good it's something of a tender trap that brings its own problems.

For three years Cat Stevens' success growth has been rapid and sure-footed. There hasn't

been a slip on the way and now with four world-wide smash albums tucked under his arm and

the knowledge of his pulling power (it transpires he could have sold the Albert Hall out

twice with no problem at all) he is in an admirably secure position some would say.

But in fact it's this very

security that he appears to be fighting with all his new found strength.

In his dressing room be

grins like a non-stop Cheshire cat. There is a friendly confusion in the air. Jean and

bass player Alan James are indulging in some fine souped up Bach/jazz improvisation; Alun

Davies is chatting with friends, Gerry Conway is drifting around as only he can - looking

earnestly as though he's just lost some important train of thought.

The band's sound man, John,

is working out who’s tuned what. On stage the Sutherland Brothers are three minutes

into the first half and their harmonies can just be heard along the corridor when someone

opens the door.

In the midst of the noise and

rabble rousing Stevens talks with great determination - sometimes having to yell across

the racket. Occasionally turning to Gerry to say - during a conversation about how the

four months on the road have seemed like one year capsuled, how HE feels he's changed.

"Not much, not me" mutters Gerry thoughtfully "You just get much more

involved in the music -there's no diversion of energies on the road".

'Right", says Stevens

enthusiastically "There's no wastage that's what it is. I think it's become very

noticeable to everyone how much I've changed. My friends really expected me to be a wreck

after the tour. They can't believe that you can do something you really dig and still come

back digging it - and I did, I really did. I feel now I have all the energy in the world.

And yet four months ago I felt drained.

" 'Catch Bull' was a

determined effort. Now I feel like I'm starting all over again with all this inexhaustible

energy coming in. It's so weird and yet, so nice. I can't explain why it's happened I'm

just thankful it has - because there's this awful fear of getting stale. All artists get

it. When something like this happens you just thank it for happening."

We get on to "Catch

Bull". Cat says he sees it as the end of a four album period but it's probably more

noticeable from that album that he was really trying to break away from a format that he's

accidentally found himself trapped in on the previous three:

"I must admit I

remember reading somewhere how alike the material had become and how only three songs

stood out. I thought at the time that the fact they didn't even consider the other seven

... well it got me a bit wild. So I thought some kind of change was in order. I'm fighting

hard now not to be too predictable in my writing and that's a danger once it becomes easy

which it has for me.

"Now I have to change

something that comes naturally and that forces me to think why I'm doing it. I think

that's why I haven't started work on a new album yet - I've got to figure out and go back

to the roots of just singing and enjoying writing. Success does affect your music and I'd

like to come out with something now that's freer and more natural and I think I

will."

Success too has affected

Stevens on a more personal level: -

"I'm very determined

not to become an institution. It's very easy to fall into that - put out a record, promote

it, do tours, interviews, all the things that are expected of you and that everyone else

does. It's hard not to and of course I take part in institutional things like everyone

else.

"In the music scene

you're branded once you start. The career tends to rule you. The Albert Hall frightened me

as being an institution, it took me a long time to make up my mind to play there.

"You see to me I only

have two involvements. One is my music and the other is my family. As my career develops

so my life with my family and. friends changes until you get to the point of saying 'well

they've accepted me for doing what I'm doing and that's what I didn't want'. I wanted to

break free of something that was already organised always - like school, art school, work.

I think that's why I've changed now - because I'm against that kind of security so much. I

just don't always want to do the accepted thing.

Energy

"No not like live

appearances. They're very important. I wouldn't stop those - that's how you keep

communication. The only time I did stop I was writing and it was all the same figures, the

same chord structures. Live is the point where all things take place. It is the one take

and you know when you're up there that if it takes off you're going to finish really well.

"I don't think people

that withdraw progress fast enough. Neil Young and Van Morrison? Yes they're both cases in

point, I really like their work but I don't feel they've progressed very much musically

and that may well be because they don't appear live enough.

"I don't think you can

ever rely on success - directly you do, it's gone. But you do need a lot of energy not to

fall into that trap. Now the way I use the success I've got and the energy I've got has to

be just right. And I feel that, maybe it's a challenge in a way and perhaps that's why I

feel this new enthusiasm so much."

Bournemouth Winter Gardens.

Full house. The rain's stopped just for an hour. Up on stage Cat Stevens is perched over

his piano, his black curls bouncing around and into "Miles From Nowhere" . . .

"I have my freedom' he rightly pounds into the mike curling his growl round it.

"I can make my own road".

|