This wonderful new article written in the Mojo

Magazine June 2000 issue comes courtesy

of Murphy Anderson.

TIME

TO MAKE A CHANGE

It's

one of music's most overdue reconciliation's.

Yusuf Islam has made peace with Cat Stevens.

By

Colin Irwin

"Just

over there was a small studio where I recorded

my first demo at Regent Sound… and there,

on the corner, that’s where my father

had his restaurant… oh, and there is

a great shop just around this corner…"

He

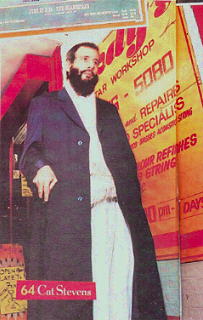

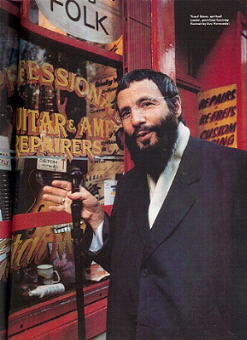

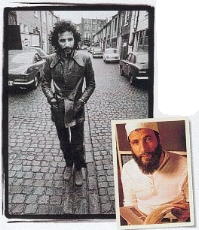

looks immaculate. A slim, slightly-built figure,

he strides with brisk purposefulness wielding

a gentleman’s cane. He is polite, formal,

charming and mildly suspicious. It’s

a major shock when he suddenly addresses you

in a voice of conspiratorial matiness and

laddish Cockney.

Yusuf

Islam – the artist formerly known as

Cat Stevens – is 52. Today, on a voyage

of rediscovery around the West End of London

where he was born and raised, he marches through

his old manor with touching boyishness. His

father, a Greek Cypriot, ran the Moulin Rouge

restaurant and is still widely remembered

locally. The proprietor of the nearby upmarket

umbrella shop is delighted when Yusuf unassumingly

introduces himself. "I remember your

father very well. Such a fine man."

"Yes,

thank you," says Yusuf humbly, genuinely

pleased. Yusuf himself remembers being enraptured

by the dazzling array of shows lighting up

theatres all over the area when he was a child.

"My greatest hobby," he says, slightly

embarrassed, "was climbing up on roofs.

I couldn’t believe it when The Drifters

did that song Up On The Roof – it was

as if someone had captured that moment and

put it in a song."

He

was always an outsider. It could scarcely

have been otherwise for the painfully shy

son of a Greek father and a Swedish mother

who went to a Roman Catholic school in Drury

Lane. He credits this unique environment as

the stimulus for the lyrical eccentricity

of early hits like Matthew and Son, I Love

My Dog and I’m Gonna Get Me A Gun –

surreal graphic cameos compared to the likes

of Pet Clark’s This Is My Song and Engelbert’s

Release Me, which were competing for the top

of the charts.

He

was, he admits, "a little weird".

His father had a piano in the restaurant "as

a status symbol" and the teenage Georgiou

turned to music and art as the only means

of expression for his awkward introversion.

He knew from an early age he had to escape.

"Everything about this place was flashing

a message to me, that I didn’t want to

work in the restaurant for the rest of my

life. My father was a wonderful man. He was

very well traveled and spoke 10 languages,

but I always knew I wanted to jump out of

the restaurant. I supposed I used music and

art to launch me."

Living

in the metropolis, he was exposed to all manner

of music and cultures. His sister’s record

collection also introduced him to George Gershwin,

Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole before a new

world opened up via Buddy Holly and Little

Richard. But it was the thriving folk scene

of the early ‘60’s which helped

to edge music above art in his escape route.

He’d abandoned one-fingered piano after

persuading his father to buy him an 8-pound

acoustic guitar when he was 15 and immediately

started writing songs. He started gigging

during a brief spell at Hammersmith College

of Art. " At first it was mainly in front

of friends. There was a little kebab shop

down the road and there was Les Cousins. I’d

occasionally pick up a guitar there but I

was too shy to play more than one or two songs."

A Greek entrepreneur arranged an audition

with producer Mike Hurst, who once had hits

of his own with The Springfields, and at 17

he was signed to Decca, who were so impressed

that they launched the Deram label –

later home to David Bowie and The Moody Blues

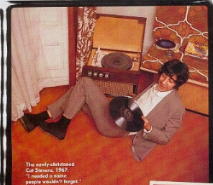

– in his honour. Steven Georgiou was

clued in enough to know that the name had

to go, and came up with Cat Stevens himself.

"I needed a name people wouldn’t

forget. My songs weren’t particularly

commercial but I was very commercially minded."

His

first single was the decidedly curious I Love

My Dog. "I love my dog as much as I lu-huff

yoooo…" with its brooding cello

and dramatic arrangement. Now what was that

all about?

"It

was actually true, that song! Not far from

here I found a little dog, one of those sausage

dogs, tied to a post outside Foyles. No one

was claiming it, so I took the dog home. The

song was about him."

A

massive turntable hit on the pirate stations

Radio Caroline and Radio London which were

revolutionizing our listening habits, it reached

Number 28 in October, 1966 but offered little

clue that it would provide the trigger for

one of the biggest international stars of

the next decade. He wrote Matthew and Son

after seeing a sign in a solicitor’s

window while riding on a London bus. By the

time he reached his stop a whole storyline

had formed in his head about the entire depressing

life of a downtrodden office worker. Only

The Monkees’ I’m A Believer stopped

Matthew and Son topping the charts in the

first weeks of 1967 and Cat Stevens –

now photographed in black velvet Carnaby Street

suits – was ready for anything. A trendy,

good-looking 18-year-old who appeared mean,

moody and a little unhinged and wrote mad

songs, he really couldn’t fail….

"It

was all very exciting," he laughs now.

"Every day there was something new, a

different challenge. I felt I thoroughly deserved

it. I lapped it up."

In

fact, he lapped it up a bit too much. By his

own admission he was often unreasonably temperamental

and avidly indulged the many excesses on offer.

He appeared in shows with Georgie Fame and

Marc Bolan ("He was too far out for me

to understand") and went on a package

tour with The Walker Brothers, Engelbert Humperdinck

and Jimi Hendrix. "Actually I got on

well with both Engelbert and Jimi. Jimi was

a very warm and friendly man, a soft-spoken

fellow and a gentle man. It was only when

he got on stage that all hell broke loose.

It was like he was on one of those rapids

– he just couldn’t stop himself.

After the show I’d mostly hang around

with Jimi and we’d go to clubs and discos,

Engelbert wouldn’t go to the same clubs

as us!" In

fact, he lapped it up a bit too much. By his

own admission he was often unreasonably temperamental

and avidly indulged the many excesses on offer.

He appeared in shows with Georgie Fame and

Marc Bolan ("He was too far out for me

to understand") and went on a package

tour with The Walker Brothers, Engelbert Humperdinck

and Jimi Hendrix. "Actually I got on

well with both Engelbert and Jimi. Jimi was

a very warm and friendly man, a soft-spoken

fellow and a gentle man. It was only when

he got on stage that all hell broke loose.

It was like he was on one of those rapids

– he just couldn’t stop himself.

After the show I’d mostly hang around

with Jimi and we’d go to clubs and discos,

Engelbert wouldn’t go to the same clubs

as us!"

Cat

Stevens lived the rock’n’roll cliché.

He drank too much, smoked too much, didn’t

eat properly and couldn’t resist a party.

But he was encountering problems with the

company suits. Already a respected writer

of hits for others (Here Comes My Baby for

The Tremeloes, The First Cut Is The Deepest

for P.P. Arnold) he disowned a violent gun-toting

poster promoting his I’m Gonna Get Me

A Gun single – a song he’d written

as part of a projected musical about his childhood

hero Billy The Kid (I’m Gonna Get Me

A Gun is conspicuous by its absence from the

latest Remember Cat Stevens collection).

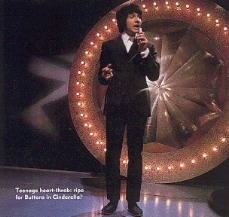

Then they suggested it would be a good career

move to go into panto and play Buttons in

Cinderella. "Tommy Steele and Cliff Richard

did that sort of thing then, but I said, No,

that’s the end."

Within

18 months he’d gone from awkward teenager

to wide-eyed pop heart-throb to disillusioned

physical wreck. Early in 1968 he caught a

cold. It turned into a nasty cough. Then he

started coughing up blood. He was rushed to

the hospital and almost died. He had pleurisy.

"Death is the great reminder. There’s

no better way to sober up than to think about

death."

Convalescing in the hospital, his writing took on an

acoustic direction totally at odds with his

previous image. The idea of a washed-up teen

idol trying to make it as a serious songwriter

seemed laughable, but Chris Blackwell had

faith and signed him to Island. He went into

the studio with ex-Yardbird Paul Samwell-Smith

as produce to record his next two albums,

Mona Bone Jakon and Tea for the

Tillerman. "Now I could do it without

the horns and the back-up session men, and

that was so liberating. In the Decca days

I was doing three tracks in a session, but

now I could spend an evening doing one track,

which showed they believed in me. Nobody was

happier than Chris Blackwell when it all started

happening." Convalescing in the hospital, his writing took on an

acoustic direction totally at odds with his

previous image. The idea of a washed-up teen

idol trying to make it as a serious songwriter

seemed laughable, but Chris Blackwell had

faith and signed him to Island. He went into

the studio with ex-Yardbird Paul Samwell-Smith

as produce to record his next two albums,

Mona Bone Jakon and Tea for the

Tillerman. "Now I could do it without

the horns and the back-up session men, and

that was so liberating. In the Decca days

I was doing three tracks in a session, but

now I could spend an evening doing one track,

which showed they believed in me. Nobody was

happier than Chris Blackwell when it all started

happening."

Cat

Stevens, now a reborn singer-songwriter who’d

swapped his old sharp suits for jeans and

T-shirts, became a huge success in America

and had a major hit with the ambitious Lady

D’Arbanville – inspired by his then

girlfriend Patti. He even provided Jimmy Cliff

with an international hit when he covered

Wild World. Peace Train, his deepest and most

telling song to date, gave him a US Top 10.

"America was a whole new experience.

The package they perceived as Cat Stevens

was very different from the UK, which knew

me as the velvet-clad young teenybopper."

Also included on Tea for the Tillerman was

Father and Son, a moving dialogue song that

took on a startling new life when Boyzone

revived it and took it to the top of the charts

in ’95. Yusuf Islam chuckles at the absurdity

of it all. If nothing else it gave him cachet

with his kids: "I wrote Father And Son

in connection with an idea I had about a musical

based on the Russian Revolution: the son was

about to join the Revolution, the father was

a farmer who wanted him to stay at home. I

was in a Turkish restaurant one day and it

came on the radio. One of my children said,

‘Dad, isn’t that your song?’

I said, ‘Why, yes it is!’ It turned

out to be Boyzone. It’s a nice version

and I’m grateful it was a clean-cut group

who did it. I went to meet them at Top Of

The Pops and we had a nice time. They’re

a good bunch of lads."

Tea

for the Tillerman ultimately spent 79

weeks in the US chart, a feat almost repeated

by its successor Teaser and the Firecat,

which included two of his most famous hits

Moon Shadow and Morning Has Broken. Today

he nominates Moon Shadow as his favourite

of the old hits for its lyrical message, while

still somewhat bemused at the way Morning

Has Broken, featuring Rick Wakeman on piano,

had become such an institution. "I found

it in a hymn book. I was looking for inspiration

and went into the religious section in Foyles

down the road and came across the song. But

I’m very surprised it took on such meaning.

It was on of the few songs I didn’t write.

Another Saturday Night was another. And one

they may want to release sometime is my version

of Fats Domino’s Blue Monday – it’s

in the vaults somewhere and they’re trying

to get it out."

By

the time he recorded Catch Bull At Four

in 1972 he was getting more and more spiritual

– the title itself was named after Kakuan’s

Ten Bulls, a 12th century Buddhist

treatise about the steps to self-realization.

The Foreigner album was even more philosophical.

A whole side was devoted to the deeply complex

Foreigner Suite; Stevens himself, meanwhile,

was becoming ever more reclusive.

As

Yusuf describes it now, the great staging

post was another near-death experience in

the mid-‘70’s. "I’d gone

for a swim at my friend Jerry Moss’s

house in Malibu and didn’t realize the

current was so strong. When I tried to swim

back to land I found I wasn’t going anywhere

– just backwards into the ocean. I feared

death again. It was that moment of truth when

we all realize how incredibly weak we are.

I called out to God and the answer came. I

was given a push and the waves suddenly turned

in my favour and I was swimming back. I’d

always believed deep down in God because I

had a private religious side. People often

do have a sense of the sacred but are too

busy with life to give it any credence. It’s

only when they really need it that they call

it up and it’s right there, right on

the surface.

His

brother David returned from Jerusalem with

a copy of the Koran, and from that point Cat

Stevens’ days were numbered. Subsequent

albums Buddha And The Chocolate Box,

Numbers, Izitso and Back

To Earth became increasingly obtuse and,

though they continued to sell to a devoted

fan base, Stevens himself became virtually

invisible, even leaving the UK to live in

Brazil at one point.

"I

was still going on tour and making music after

I became a Muslim. There’s nothing in

the Koran to forbid music, it’s just

showing off that’s not accepted. God

must be the object of our devotion, but music

isn’t banned. But there is a certain

school of thought which looks upon music and

entertainment as something frivolous, so I

stared to think again. There is music in the

Muslim world but I didn’t make the equation.

I was looking strictly at scripture interpretation,

and it took me a long time to understand the

differences. So I decided to make the break."

In

1979, Cat Stevens ceased to be. He auctioned

off his guitars, gave the money to charity,

changed his name to Yusuf Islam and announced

that his music career was over and that he’d

be dedicating the rest of his life to Islam:

"The only thing I regret was the way

I did it. I was unable to express myself and

perhaps it looked illogical and bizarre. I

was trying to convey the message that this

was what was important to me now and I hoped

it would also be important to people who liked

my music and listened to my words. But I was

so wrapped up in my new life I didn’t

give enough time to try and explain myself.

Perhaps I needed to feel comfortable as a

Muslim. It’s not an easy thing to do.

"Islam

is still looked upon as something alien to

the Western way of life but what I was discovering

was that all the incredible links that make

us human and provide us with optimism and

hope for tomorrow are all in Islam. Explaining

that to someone else is very difficult."

Still

regarded with suspicion by many Westerners,

Yusuf has worked vigorously in his new role.

In 1984 he set up Muslim Aid for famine relief

in Africa; in 1990 he went on a peace mission

to Iraq and successfully returned with four

hostages. He runs an Islamic hotel in Willesden

and is also passionately involved in education

both as a teacher and in setting up schools

for the Muslim underprivileged. One of his

proudest achievements recently has been to

get state aid for one of them. "I was

on my way to Sarajevo when I got the news.

I’d landed in Vienna and they rang and

said, ‘We’ve got it!’ I jumped

into the air."

He

also started recording again. He released

The Life Of The Last Prophet in 1995,

a 65-minute 2-CD mainly spoken word biography

of the Prophet Muhammad, but it took the Bosnian

conflict to shock him into writing and singing

a brand new song, The Little Ones – accompanied

only by drums – featured on the I

Have No Cannons That Roar collection of

Bosnian music dedicated to the children of

Sarajevo and Dunblane. Bosnia’s foreign

minister Irfan Ljubijankic had given Yusuf

a Bosnian song and asked him to "do something

with it". When Ljubijankic was killed

in the war shortly afterwards, Yusuf knew

he must complete the project. He has another

new album, A Is For Allah, just released

on his own Mountain Of Light label, and has

also published a beautiful book of the same

title.

Most

surprising of all, though, is his active involvement

in an ongoing Cat Stevens reissue programme:

"My view of my past has changed since

I embraced Islam. In the early days I wanted

to forget about it and move on. But now I’ve

come to a more balanced view of my music.

There’s good and bad in it, but there

are still some messages and words that are

valid today so I look on the positive side.

"I

received a letter recently from somebody who

said she was on the verge of suicide, but

heard my music and it changed her mind. She

was about to end it all but saw hope through

my songs. That’s good enough for me." |