LONDON

TIMES Friday November 12, 1999

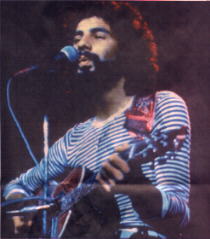

Cat Stevens was one of the

most popular musicians of the Seventies. Twenty-two years ago he turned his back on the

music business and became a devout Muslim. Today, as Yusuf Islam, he has finally

acknowledged the value of his earlier career and admits that he regrets losing contact

with people he cared about. Interview by Nigel Williamson

Cat Stevens: Cat Stevens:- I miss being able to sing to people

It was more than 20 years

ago that the young Cat Stevens sang "Remember the days of the old schoolyard".

Today, as Yusuf Islam, he stands on a grey November afternoon in the playground of one of

the four Islamic schools in North London that are funded by the profits from his

long-abandoned pop career.

"I wrote a song once

about a schoolyard not unlike this," he says softly before his voice trails away. The

sentence is unnecessary, for everybody remembers it. He wrote another equally well-known

song, Where Do The Children Play? Then there was Father and Son, Oh Very Young,

Moonshadow and Tea For The Tillerman, all of which made him one of the most

popular singers of his generation.

Yet to the dismay of his

fans, Stevens embraced Islam in 1977. His conversion was not of the faddish pop star

"this-week-I'm-a-Buddhist" school. He adopted his new faith hook, line and holy

rote, turning his back on his old life with the zeal of the convert. He auctioned his

guitars and gold records for Islamic charities, changed his name and denounced his old

songs as akin to blasphemy. Worse, he became associated with the most fiercely

fundamentalist forms of Islam, a stern and humourless dogmatist, apparently intolerant of

those who did not share his faith.

That he has brought us to

the old schoolyard because it reminds him of a pop song he wrote long ago represents a

significant softening of the hard line. At 51, more than two decades after the

denunciation of his former existence, it seems that he has learnt to live with his past.

"As I look back at

those songs they are an open book," he says. "It was a time of learning and

growing. When I first embraced Islam I rejected everything. I wanted to make a clean break

with the past. But on reflection there are many things in those songs that remain true

today. My music still stands as something gentle and meaningful and significant."

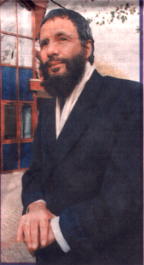

It is a profound moment.

The first time in 22 years that Yusuf Islam and Cat Stevens have publicly kissed and made

up. The patriarchal beard is imposing but with a shave he could pass for a man much

younger. There is an almost boyish twinkle in his eyes and his skin is incredibly smooth.

He is dressed in khaki cords with neat turn-ups, brown loafers and a calf-length coat. He

carries a walking cane.

Softly spoken and

courteous, after we have walked around the school (at which his 17-year-old son Mohammed

is a pupil), he drives his shiny 4x4 to the Islamic hotel that he owns near by in

Willesden. This was once a police hostel; he turned it into an hotel three years ago.

Rooms start at £36 per night and the profits are ploughed into a trust to sustain his

schools. Usury is banned under Islamic law so he cannot leave his money accumulating

interest in a bank. Putting capital to work in other ways, however, is encouraged.

This week his old record

company releases Remember Cat Stevens, a 24-song collection of his best-known hits.

In the new year - to coincide with the end of Ramadan - he will release his own new

record, A Is For Allah. It will be accompanied by a children's book of the same

name, which he thrusts into my hands. "I don't think I ever said popular music was

blasphemous. But there are two opinions in Islam. The common view of most scholars is that

you should stay away from music and frivolous activity. But there are other scholars who

say that the Prophet allowed music at certain times and on special occasions. It took me

all this time to get to that balance of understanding," he says.

He was born Steven Dimitri

Georgiou, to a Greek restaurateur and a Swedish mother. He grew up in London's West End

and went to a Roman Catholic school in Drury Lane. His first hit came in 1966 when he was

19; pictures from the time show a foppishly handsome young man given to dressing in lace

and crushed velvet. He enjoyed the life of a Sixties pop star to the hilt, partaking

liberally of the drink, drugs and girls that went with the territory.

Then in 1968 he contracted

tuberculosis. In retrospect, this was the wake-up call that changed his life. When he

emerged from hospital a year later he was much changed, reinventing himself as a sensitive

troubadour rather than the brash Top of the Pops hip-wiggler he had been.

"People have times in their lives when they are forced to examine themselves -

trauma, illness, accidents. You stop and think 'it could all disappear tomorrow and where

would I be?' That was the beginning for me of that process of thought."

A series of gold albums

followed throughout the Seventies. Their phenomenal success eventually forced him into tax

exile in Brazil for a year, although he donated the money he saved to Unesco. Increasingly

his songs displayed an interest in the spiritual, most obviously his arrangement of the

children's hymn Morning Has Broken.

He recalls an occasion when

he nearly drowned while swimming off Malibu Beach and cried out to God to save him. The

tide that was washing him out to sea turned and he took it to be a sign. Yet he found no

answers in the Bible and it was not until his brother David gave him a copy of the Koran

in 1977 that he found his new direction. By the end of the year he had changed his name

and given up his career.

"What I was really

rejecting was the business - agents, record companies, the rat race, competitiveness. I

didn't want to stick around in that environment. I was just happy to have the keys to get

out."

But his fans felt rejected,

particularly by the ferocity with which he denounced the songs they loved. Today he has

come to regret the fierceness of his attitude. "It was the rush of liberty. I had

been talking and singing about freedom and here it was. I could break free from the

machinery that was choking me. But I do regret losing contact with the people I cared

about the most and who I think cared about me the most - not people who were making money

out of the music but people who were listening to it."

A recent letter from a

female fan telling him that one of his songs had saved her life seems to have softened his

attitude further. "She had been suffering from depression. She said one of the songs

had helped her to regain her faith. That's positive."

He has also been surfing

the Internet websites devoted to him and seems touched by the affection in which he is

still held. "I turned my back and I can see how the fans felt. There was a breaking

of the connection between souls, and that was the biggest sadness for me - which is why I

am now happy to reconnect and say to people I haven't really gone that far away. I'm ready

to communicate and I don't want to lose touch."

There is some routine

blaming of the media for the reaction that greeted his conversion. "It was 'Islam -

what is that?' And the Ayatollah came into the picture at the same time and I was

overwhelmed. I was treated like an alien."

He is still mistrustful of

the media and I was carefully vetted before he agreed to be interviewed. An article I had

written about Sufi music which had criticised the negative stereotyping of the

Islamic world had apparently done the trick. But did not some of his own comments

contribute to the negative image of Islam - in particular when he appeared to endorse the

fatwa on Salman Rushdie in 1989?

"The connection with

the fundamentalists was accidental and maybe that was intentional on the part of the press

too. They prefer to take a particularly microscopic view of Islam and mist over the larger

picture. That issue wasn't really connected to me and I had very little to do with

it."

He even blames the press

for the infamous book-burning in Bradford. "It was the journalists who first

suggested to the protesters to burn the book to get a good picture. It was about a photo

opportunity and a headline, and it created a crisis. There was an immense amount of

civilised protest that took place before that and I hope I represent mainstream Islam. But

the media is not interested in simple Muslims who go about their lives getting up to pray

at five in the morning and fasting. There has to be sensation."

But it depends, surely, on

your definition of mainstream? Yusuf Islam is a firm advocate of banning alcohol and

gambling, which is hardly a moderate position.

"The biggest problem

is not drinking or gambling. It's a re-examination of the human being as he should be.

That means a connection with the divine. In gambling the majority lose and very few win.

Yes, we do want to ban drinking. Every doctor will tell you that it is damaging to health

and to society. You know how many wives get beaten up because the men are drunk."

These are the areas where

the flashpoints are most combustible between Western liberal opinion and Islam. Gambling

and drinking may be damaging pursuits but whatever happened to free will?

"We didn't come about

by our own will," he replies. "There is a higher will that brought us here and

you have to recognise that presence which is God." It is the sort of circular

argument that is difficult to counter because you can't break into its self-supporting

internal logic. Particularly when he maintains that Islam is not a prohibitive creed.

"In Islam the general rule is that everything is allowed except the things that are

forbidden."

He has one son and four

daughters by his wife, Fouzia Ali, whom he married in 1979. He is not, he says, a strict

father. "I don't think you can be these days. The society in which you live dictates

the general culture, even in the home. You have to be more lenient and be a friend to your

kids."

Yet his daughters, all

educated in his schools, wear the veil all the time. "It's basic modest dress as you

would have found everywhere in England not long ago. The veil protects family values.

There is this natural instinct when we see a beautiful woman to gawk. The veil is to stop

that.

"If the family breaks

down society is lost. Maybe the next generation will turn more puritanical. Things have

slipped so far it may be the time for that. I'm happy that my children have taken a look

at society and said 'you're right Dad, it's pretty bad out there'."

Semi-arranged marriages are

already under discussion for his daughters, although they will have the right to say no.

"We're consulting now. I had a choice of two wives and I introduced them to my mother

and asked her. I knew marriage was not just a selfish thing between two people but about a

bonding between families. So I wanted to make sure my mother had a say."

Although he was then 30, he

married her choice. Does love play a part? "Of course. We believe that love really

blossoms after marriage but there has to be attraction. It's the miracle of life and you

can't deny it. But it has got to be guided and God has given us rules for that."

He lives with his family in

Willesden in a style he describes as "moderate". He would take the bus if he had

more time, he insists. He recently took the train to Cambridge and found himself on the

Tube in rush hour. The experience sent him flashing back to Matthew & Son,

about commuter alienation.

"There are so many

people still on that line. I miss those issues, to be able to sing about them and give a

little boost to someone who feels lost."

He doesn't own a guitar and

says he doesn't even sing in the shower. "But sometimes I remember song lyrics.

Backstabbers by the O'Jays suddenly came into my head the other day. There's a lot of

people out there stabbing each other in the back." He singles out Moonshadow

from his own work. "It is a highly prophetic song. It says no matter how bad things

are there is always a positive side. I believe that is part of the legacy of my songs. I'm

glad about that."

What we have just witnessed

is the rehabilitation of Cat Stevens in the eyes of his sternest critic. Yet clearly the

process hasn't yet gone far enough for Moonshadow to be played in the hotel lobby.

As we take our leave the appalling strains of Muzak float across the hall. The tune is Don't

Cry For Me Argentina.

|